Charleston Renaissance: Alfred Hutty

Come quickly, have found heaven!

This is the telegram that Alfred Hutty is said to have sent to his wife upon his first visit to Charleston. Though he was not originally from South Carolina, Hutty’s paintings, drawings, and prints of Charleston’s urban areas and surrounding lowcountry landscapes showcase his love for the area, and his work with fellow local artists in the 1920s and 30s earned him recognition as one of the leaders of the Charleston Renaissance.

Alfred Hutty was born in Grand Haven, Michigan in 1877. He exhibited artistic skill from a young age, and earned a scholarship to study stained glass design at the Kansas City School of Fine Arts. However, due to his family’s financial situation, he was unable to take advantage of the scholarship and instead worked in a stained glass factory in Kansas City. When he married in 1902, he and his wife Bessie moved to St. Louis. Here he met painter L. Birge Harrison, and Alfred and Bessie soon moved to Woodstock, NY, where Hutty could take lessons from Harrison. Hutty worked at Tiffany Studios in New York to earn money, and continued to study art techniques: painting from Harrison and Frank Vincent DuMond, and life drawing from George Bridgman.

During World War I, Hutty served as an artist camouflaging marine vessels. After the war, he visited Charleston and was so taken with the city that he is said to have called for his wife to come join him immediately. They moved to Charleston, and from 1920-1924 Hutty served as the director of the Carolina Art Association, what would later be known as the Gibbes Museum of Art. Here, he connected with local artists including Alice Ravenel Huger Smith, Elizabeth O’Neill Verner, and Anna Heyward Taylor. This group formed the core of the visual arts aspect of what would come to be known as the Charleston Renaissance, a period in the 1920s and 1930s of growth in local arts, culture, history, and historic preservation.

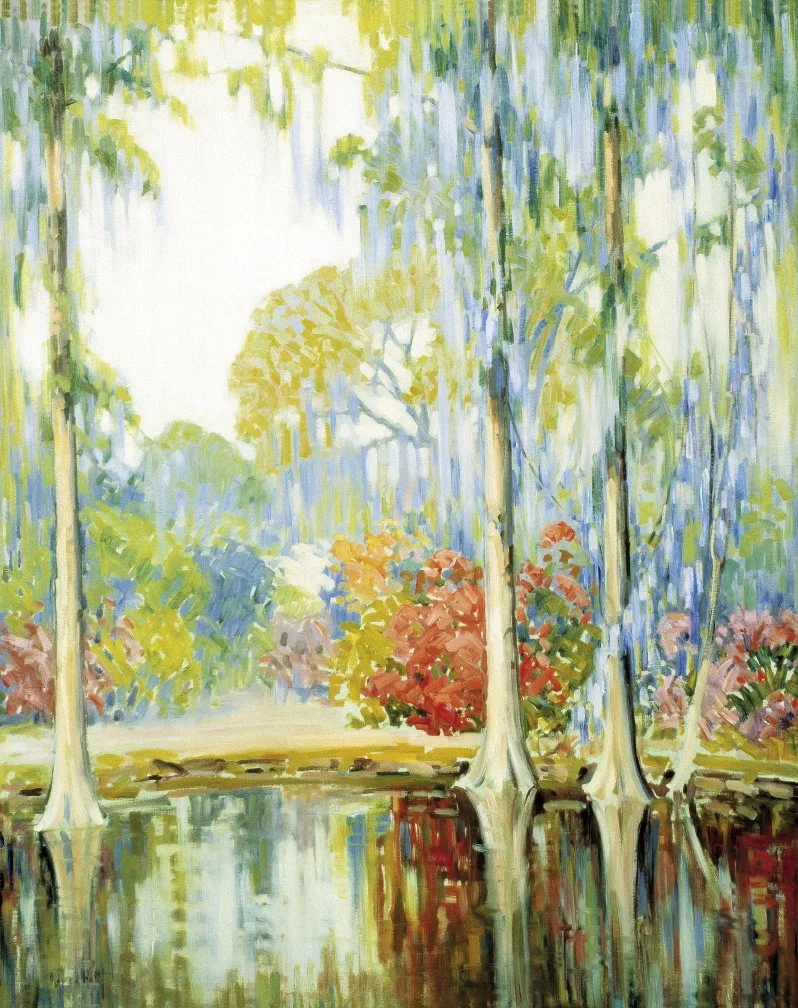

Hutty’s work focused on straightforward views of daily life in Charleston, as well as expressive, impressionistic landscapes of the surrounding lowcountry. As an outsider, he tended to offer a less romanticized view of Charleston than many southerners, depicting in detail the rich textures and variegated colors of the parts of the city prone to decay: the back sides of buildings, with their sagging roofs, crumbling bricks, and cluttered lines, were a common motif in his work, often labeled “backstage.” While he certainly did create images of the city’s elegant facades, the details and textures of working-class life - in particular, the everyday scenes of African-American Charlestonians - seemed to most catch and hold his attention. The result is an interesting, if incomplete, record of Charleston: while his lowcountry is not idealized and he does not shy away from depicting the poverty and decay common in the region in the interwar period - especially as it affects the local African American community - neither does he address the pressing social concerns of the time. His depictions of African Americans fall flat, characters on a stage - contrast with Elizabeth O’Neill Verner’s vibrant portraits of African American women working on the city’s streets.

Charleston and its surrounding landscapes are uniquely depicted in Hutty’s paintings, drawings, etchings, and prints. His style incorporates elements of Realism, an art movement that embraced scenes of everyday life without idealization; as well as impressionistic techniques, with a focus on the interactions of light, shadow, and colors within a scene. There is an obvious delight in his drawings in depicting the textures of the lowcountry: crumbling brick and stucco, swirling ironwork, dappled light through great live oak trees draped with the curls of Spanish moss. And his paintings emphasize a sort of softness and stillness in their images of flowering plants, empty gardens, sunlight on a courtyard wall.

The Charleston Renaissance was a period during which art became a tool and channel through which to shape public opinion on Charleston, and to inspire action to preserve the city’s historic and cultural treasures. The works of artists such as Hutty both reminded locals of the beauty around them, and inspired outsiders to visit, sparking the beginnings of the city’s tourism industry. In changing the way we see our surroundings, we can change the course of its history - and the Charleston Renaissance is a fantastic example of this.

We’ll be back soon with more discussion of the Charleston Renaissance!

More South Carolina Artists:

Alice Ravenel Huger Smith | Elizabeth O’Neill Verner | Ned Jennings | William Halsey | Jasper Johns | Merton Simpson