South Carolina Artists: Ned Jennings

Charleston has long been a hub of creative arts and vibrant culture, and we’re diving into profiles on some of the artists who have been most influential upon - and influenced by - the Holy City. We’re kicking off this series with Ned Jennings, an artist of the Charleston Renaissance era who was one of the first in the region to experiment with cubism, abstraction, and surreal art.

Ned Jennings - born Edward I.R. Jennings in Washington, DC - was an influential artist of the Charleston Renaissance, and one whose story we share on our Real Rainbow Row tour.

Jennings’ family moved to Charleston when he was a child, and his father served as the city’s postmaster. Ned briefly served in WWI, but was injured by poison gas and spent time recovering in England before returning to South Carolina. Back in his hometown, he studied at the College of Charleston before transferring to Columbia University in New York. There, he studied art, design, and stagecraft; he also spent some time in Paris studying under the private tutelage of painter Mela Muter.

Back in Charleston, Jennings became involved in the city’s arts and culture scene, working as a set designer for local theater productions and events. He found work at the Charleston Museum as the children’s curator, and used his skills to create interpretive displays and whimsical art as teaching tools. Mentored by Laura Bragg, Jennings continued to develop his own distinctive art style outside of his work for the museum.

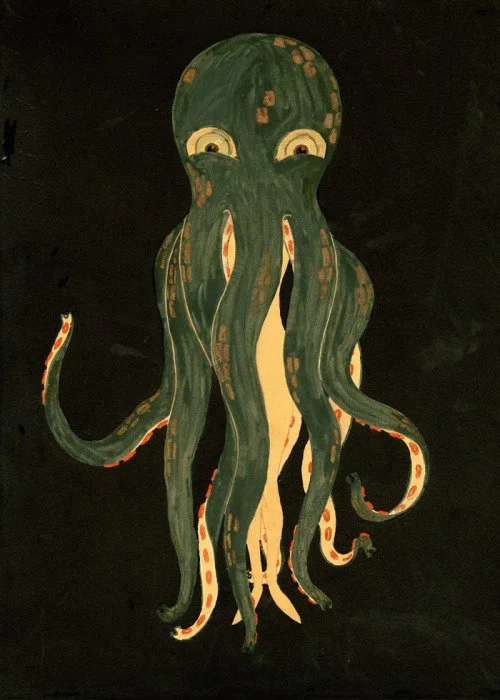

Jennings was one of the first artists in Charleston to create work influenced by cubism, surrealism, and modernist ideas. His work could be by turns lighthearted and whimsical - keeping in mind his audience of children educated by museum displays - or surreal and unsettling, veering toward the darker aspects of modernism and abstraction. His constructed sets and imaginative stage masks also became recurring themes in his personal work. Today he’s remembered as one of the pioneers of the Charleston Renaissance, the interwar period during which Charleston’s arts scene flourished, as well as an influence on later artists such as William Halsey, one of Charleston’s great abstract artists.

Jennings kept an art studio at the Confederate Home at 62 Broad St. It was here that, after the tumultuous end of his relationship with a young man (whose identity, while guesses have been made, has not been confirmed), Jennings took his own life. In May of 1929, he was found by his friends, staged with a bible and empty bottle of champagne, with a gun in his hand, surrounded by his masks.

His work was saved by Laura Bragg, who feared that it would be destroyed by others for its exploration of taboo subjects and imagery. While much of his personal work featured fantasy figures and illustrations for children, some works also explored his homoerotic feelings and societally-induced shame; dreamy abstractions whose topics were ones for which society could condemn him even after his violent death.

While his story ends in tragedy, Jenning’s lively, inspired artwork influenced future generations of artists in Charleston as he explored new ideas, and showcased a unique view of the world. His work can be seen at the Gibbes Museum of Art, and will be featured this fall and winter in an exhibition exploring the influence of the aesthetic movement on Charleston artists.

Other artists in this series: